Pattern Matching

Regex

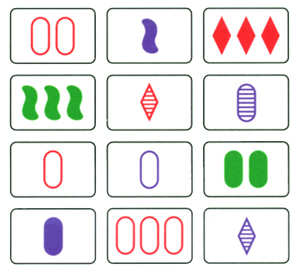

If any of you have played the card game of Set, then you will know that it is a pattern-matching game based on some basic rules. The rules for matching three cards are:

- The color on the three cards must always or never match.

- The number of shapes must always or never match.

- The fill of the shape must always or never match.

- The type of shape must always or never match.

Based on these rules, how many sets can you find in these 12 cards? People are able to internalize the rules to solve this pattern-matching problem. How can a computer perform a similar process?

Regular expressions (regex) give you a way to define your own matching rules for text. Regex is a powerful tool that lets you define exactly how you want to search and match subsets of text. If you’ve used a basic “find” feature in your word processor or browser, then you have a basic idea of the purpose of regular expressions, except rather than finding specific phrases, you define patterns.

There are several practical applications of Regex:

- Filter spam

- Search large texts

- Detect computer virus signatures

- Find patterns in DNA sequences

- Validate input on a website form

- Search-and-replace in a word processor

But why is it useful in supercomputing? Scientific computing workflows usually involve huge amounts of data. Regular expressions can be used to:

- Filter out irrelevant data

- Locate relevant data

- Detect errors in data

Regex examples can be very brief:

^\S+@\S+$ # matches an email address if it's just an '@' surrounded by non-whitespace

…or not:

The real email regex

(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:(?:(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*|(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)*\<(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:@(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*(?:,@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*)*:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)?(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*\>(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)|(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)*:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:(?:(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*|(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)*\<(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:@(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*(?:,@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*)*:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)?(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*\>(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:,\s*(?:(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*|(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)*\<(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:@(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*(?:,@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*)*:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)?(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|"(?:[^\"\r\\]|\\.|(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t]))*"(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*@(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*)(?:\.(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*(?:[^()<>@,;:\\".\[\] \000-\031]+(?:(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])+|\Z|(?=[\["()<>@,;:\\".\[\]]))|\[([^\[\]\r\\]|\\.)*\](?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*\>(?:(?:\r\n)?[ \t])*))*)?;\s*)

Regex engines are common throughout command line tools, text editors, and programming languages. However, a given tool or programming language will implement a particular regex engine. Regex engines may differ slightly in syntax and supported features. It’s important to learn the basics of regex, and to know how it’s used in your specific context.

There are many regex engines; the most commonly used are:

- Perl: The gold standard for regular expressions

- PCRE: “Perl Compatible Regular Expressions” A C library inspired by Perl. Used by PHP, Julia, and R.

- POSIX: Used for common Linux commands such as

grep. It comes in basic and extended flavors. One of the oldest and most limited regex engines still in use today.

If you’re doing anything serious, you’ll want something stronger than POSIX regex, although it’s fine for very simple pattern matching.

Regex Golf is a good place to practice with regular expressions.

Examples

Metacharacters

| Metacharacter | Meaning | Example | Would Match | Wouldn’t Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

^ |

start of line | ^persian |

persian cat | my persian cat |

$ |

end of line | persian$ |

he is persian | is he persian? |

. |

any one character | ca.d |

rock candy | cared |

? |

zero or one of | flavou?r |

flavor, flavour | flavouur |

+ |

one or more of | flavou+r |

flavouuuur | flavor |

* |

zero or more of | flavou*r |

flavor, flavouuur | flavoor |

{x} |

x of | fla{3}vor |

flaaavor | flaaaaavor |

{x,y} |

x to y of | fla{2,4}vor |

flaavor, flaaaavor | flavor, flaaaaavor |

{x,} |

x or more of | fla{2,}vor |

flaavor, flaaaavor | flavor |

{,y} |

up to y of | fla{,4}vor |

flavor, flaaaavor | flaaaaaaaavor |

| |

alternation | cat|dog|bug |

cat, dog, bug | caog |

[xyz] |

any of x, y, z | ^[0-9A-F]+$ |

A048C1, 74F89A | N4R9V3 |

[^xyz] |

any but x, y, z | ^[^aeiou]+$ |

lynx, tsktsk | links |

() |

grouping | 0x(00|FF) |

0x00, 0xFF | 0x0F |

\ |

escape | x\{2\} |

x{2} | xx |

Shorthand:

| Class | Meaning | Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

\w |

A “word” | [A-Za-z0-9_] |

\W |

A “non-word” | [^\w] |

\s |

A space | [\t\r\n\f] |

\S |

A non-space | [^\s] |

\d |

A digit | [0-9] |

\D |

A non-digit | [^\d] |

grep, sed, and awk

grep, sed, and awk are discussed in more detail below. You don’t need to know their functionality intimately, but you should be familiar with their basic usage and common use cases.

grep

grep is the most commonly used pattern-matching tool on Linux. It’s intended for basic single-line matches. Its default regex engine (POSIX Basic) is very limited. Users can invoke different flavors of regex to get the effect you want.

| How pattern is interpreted | grep command option |

|---|---|

| POSIX Basic (default) | grep |

| POSIX Extended | grep -E |

| Fixed Strings (no regex) | grep -F |

| Perl Regex (experimental) | grep -P |

In GNU grep (what you’ll find on most Linux distros), there’s no difference between grep and grep -E, although basic grep is less powerful on some systems.

sed

The man page for sed calls it a “stream editor for filtering and transforming text”. sed’s main role is line-by-line editing of files and streams. The structure of a sed command is: sed [flags] '[address] command' [file or text]. Here is an example with the substitute command:

$ sed 's/hi/hello/' <<< 'hi, my name is John

I like hills

line with naught to replace'

hello, my name is John

I like hellolls

line with naught to replace

sed executes commands on each line of input by default. It can be used as a rudimentary language (it has branching), but if you find yourself using it as more than a line-by-line editor, you should probably just use awk.

Addresses

Check out the “Addresses” section of sed’s man page for a succinct and clear definition.

If only a command is given, it will be executed on every line. If you prefix that command with an address, you can limit its execution to those lines. There are several types of addresses. Below are examples that use the following file, lines.txt:

lines.txt:

this is line 1

now line 2

the 3rd line

line number 4

5th line here

This is the 6th line

/regex/: lines containing the regex

$ sed '/[Tt]his/ s/line/LINE/' lines.txt

this is LINE 1

now line 2

the 3rd line

line number 4

5th line here

This is the 6th LINE

number: the numberth line

$ sed '4 s/line/LINE/' lines.txt

this is line 1

now line 2

the 3rd line

LINE number 4

5th line here

This is the 6th line

n1,n2: lines n1 through n2

$ sed '3,5 s/line/LINE/' lines.txt

this is line 1

now line 2

the 3rd LINE

LINE number 4

5th LINE here

This is the 6th line

first~step: every stepth line, starting at first

$ sed '2~3 s/line/LINE/' lines.txt

this is line 1

now LINE 2

the 3rd line

line number 4

5th LINE here

This is the 6th line

$: the last line

$ sed '$ s/line/LINE/' lines.txt

this is line 1

now line 2

the 3rd line

line number 4

5th line here

This is the 6th LINE

sed Commands

Substitute is probably the most used feature for sed. The examples above were all examples of substitute. The general syntax for using substitute is s/old/new/. This will replace the first instance of “old” with “new” on each line.

$ echo "this is old, really old" | sed 's/old/new/'

this is new, really old

If you want to replace all instances, add g to the end without specifying an address:

$ echo "this is old, really old | sed 's/old/new/g'

this is new, really new

Say you want to replace a filepath–using / as separators in sed would be confusing. Fortunately, you can use other separators other than /. You can use pretty much any character, even letters and numbers. For example, commas: sed 's,/file/path/before,/the/new/path,' myscript.sh will replace the first occurrence of /file/path/before with /the/new/path on each line in myscript.sh.

You can also replace regexes with sed: sed -E '/^Phone:/ s/[0-9]{7}/REDACTED/g' sensitive-info.txt. You’ll want the -E flag when using non-trivial regexes. However, this is a pretty weak phone number regex–as a thought exercise, what could be done to improve it?

& can be used to mean “the part of the line matching the pattern”:

$ echo 'this is a line' | sed 's/.*/LINE 1: &/'

LINE 1: this is a line

$ echo 'this is a line' | sed /s/line/LINE 1: &/'

this is a LINE 1: line

$ echo 'this is a line' | sed 's/.*/& (the first one)/'

this is a line (the first one)

.* in this context just means the whole line–any amount of any characters.

This is a useful feature if you want to do something like put quotes around a certain phrase:

$ sed 's/[Ss]mart|[Ll]ogic/"&"/g' i-am-very-smart.txt

I am quite "smart", so "smart" I got a 164 on a very reputable online IQ test

"Smart" is a way of life for me

Nobody really understands me because of my intellect

Only the truly enlightened believe me when I tell them that "logic" shows that the Earth is flat

It’s also possible to match pieces of a pattern with \1, \2, etc.

$ echo "First: Pam, Last: Beasley

First: Dwight, Last: Schrute

First: Jim, Last: Halpert" | \

sed -E 's/\s*First: (.*),\s+Last: (.*)/\2, \1/'

Beasley, Pam

Schrute, Dwight

Halpert, Jim

Grouping is done with parentheses—enclose everything you want to use as a \# with parentheses. This also means if you want to use a literal parenthesis, you’ll need to escape it with \.

The following commands reference hex.txt:

d6c2

75bf

cb21

84a7

The i command inserts a line above each applicable address:

$ sed '/^[0-9]/ i STARTS W/ DIGIT:' hex.txt

d6c2

STARTS W/ DIGIT:

75bf

cb21

STARTS W/ DIGIT:

84a7

You can leave off the pattern, in which case each line of the original file or input will be preceded by the inserted string.

The a command inserts a line below each applicable address:

$ sed '/^[0-9]/ a ^STARTS W/ DIGIT' hex.txt

d6c2

75bf

^STARTS W/ DIGIT

cb21

84a7

^STARTS W/ DIGIT

d deletes a line from the stream:

$ sed '/^[0-9]/ d' hex.txt

d6c2

cb21

You can also negate deletion with !, as in “delete everything but”:

$ sed '/^[0-9]/ !d' hex.txt

75bf

94a7

The q command quits sed after encountering the first match:

$ sed '/^[0-9]/ q' hex.txt

d6c2

75bf

The p command prints a line. It is almost always combined with the -n flag, which means “suppress automatic printing”. The sed -n 'address p' command is a common way to only output a few lines.

You can also chain together multiple commands to be executed on the same address by putting multiple commands, separated by semicolons, in braces:

$ sed -n '/^[0-9]/ {p;q}' hex.txt # this command means "when you find a line starting with a digit, print that line then quit

75bf

-i and -i.bak allow editing in place. This means that nothing is printed, but the specified file is modified. sed -i 's/dog/cat/' pets.txt is equivalent to sed 's/dog/cat/' pets.txt > pets.txt.

You can also use -i.bak to save the original file as original-name.bak:

$ ls

names.txt

$ sed -i.bak 's/[Jj]im/Jimothy/g' names.txt

$ ls

names.txt names.txt.bak

awk

Say your software outputs 200,000 files, each with 10,000 lines. Each line has two numbers: an ID and a value. You need to find the smallest value and its associated ID. Most researchers would reach for awk to do so.

Of the three main Unix text processing utilities (grep, sed, awk), awk is the most versatile and powerful. Ultimately, an awk program only does two things:

- Matches a pattern

- Performs an action on the line that matched the pattern

The pattern comes first, the action is enclosed in braces: pattern { action }.

How awk Works

awk processes its input line-by-line, with each line being called a record. Each record is split into fields for processing. If pattern is true for a record, then { action } is performed.

In the following file, each line is a record:

April 8.00 15 Student # record 1

Bill 10.00 30 Student # record 2

Charlie 7.50 20 Student # record 3

Record 1 contains the following fields:

- April

- 8.00

- 15

- Student

To refer to a specific field within a pattern or { action }, you use the following syntax:

$1refers to Field 1$2refers to Field 2$3refers to Field 3, etc.$0refers to the current record (the whole line)

A One-liner Example

We have a text file named employees.txt with data in four columns:

- Employee Names

- Hourly Wage

- Hours Worked

- Whether the Employee is Student or Staff

April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

Diane 12.00 40 Staff

Ed 7.25 0 Student

Frank 15.00 35 Staff

Gilbert 7.25 20 Student

Harry 12.75 40 Staff

Isabel 7.25 15 Student

Janet 20.00 40 Staff

Kevin 16.00 40 Staff

How can we calculate the pay of each student employee who worked at least one hour?

$ awk '$4 == "Student" && $3 > 0 { print "Pay", $1, "$" $2 * $3 }' employees.txt

Pay April $120

Pay Bill $300

Pay Charlie $150

Pay Gilbert $145

Pay Isabel $108.75

You can write a longer program that the awk command line tool can read the program in from:

{ pay = pay + $2 * $3 }

END { print NR, "employees"

print "total pay is", pay

print "average pay is", pay/NR

}

When there is no pattern, a block (e.g., the first line of calculate_pay.awk) is executed for every record. The END block is executed after all lines have been read; you can also put a BEGIN block before everything else to initialize variables, etc. You can call an awk script with awk -f:

awk -f calculate_pay.awk employees.txt

If you have a brief program, it can be given inline as the first argument:

awk '/40/ { print $1 }' employees.txt

# outputs those employees with 40 hours of work

Diane

Harry

Janet

Kevin

When a pattern is omitted, awk’s default behavior is to perform the action on all lines. This is useful for extracting values from predictable text for putting it in an Excel sheet, for example.

Customizing awk

Literal strings can be printed in an action, e.g. { print "Line: " $0 }:

April 8.00 15 Student --> Line: April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> Line: Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student --> Line: Charlie 7.50 20 Student

In patterns, a field can be compared to a number or a string:

$2 > 9 { print $1, "makes more than $9 an hour" }

April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> Bill makes more than $9 an hour

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

$4 == "Student" { print $1, "is a student." }

April 8.00 15 Student --> April is a student.

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> Bill is a student.

Charlie 7.50 20 Student --> Charlie is a student.

Diane 12.00 40 Staff

When an action is omitted, awk’s default behavior is to print each matching record:

$4 == "Staff"

April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

Diane 12.00 40 Staff --> Diane 12.00 40 Staff

Ed 7.25 0 Student

Frank 15.00 35 Staff --> Frank 15.00 35 Staff

NR (Number of Records) keeps track of the number of records read so far:

{ print $1, "is on line", NR }

April 8.00 15 Student --> April is on line 1

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> Bill is on line 2

Charlie 7.50 20 Student --> Charlie is on line 3

NF (Number of Fields) contains the number of fields of the current record:

{ print "This record has", NF, "fields" }

April 8.00 --> This record has 2 fields

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> This record has 4 fields

Charlie --> This record has 1 fields

A record can be tested against a regex enclosed in forward slashes. A single field can also be tested with the ~ operator:

/^[AEIOU]/ { print $1, "starts with a vowel" }

April 8.00 15 Student --> April starts with a vowel

Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

$2 ~ /^[0-9]+\.00$/ { print $2, "is a whole dollar amount" }

April 8.00 15 Student --> 8.00 is a whole dollar amount

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> 10.00 is a whole dollar amount

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

Computations can be performed on fields:

{ print "Money Earned: $" $2 * $3 }

April 8.00 15 Student --> Money Earned: $120

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> Money Earned: $300

Charlie 7.50 20 Student --> Money Earned: $150

By default, commas in a print statement will print a space between items. If no comma is given, the two items are concatenated:

{ print $1, $4 }

April Student

Bill Student

Charlie Student

{ print $1 $4 }

AprilStudent

BillStudent

CharlieStudent

Multiple pattern-action pairs can be given:

$2 > 9 { print } $4 == "Student" { print }

April 8.00 15 Student --> April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> Bill 10.00 30 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student

# prints twice since it matches both patterns

Charlie 7.50 20 Student --> Charlie 7.50 20 Student

Diane 12.00 40 Staff --> Diane 12.00 40 Staff

Multiple patterns can be combined in a single pattern-action pair. Use && for AND, || for OR, and ! for NOT:

$2 > 9 && $4 == "Student" { print }

April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

Diane 12.00 40 Staff

The special pattern BEGIN matches before the first line:

BEGIN { print "Name Wage Hours Emp-Type" } { print }

[Start of File] --> Name Wage Hours Emp-Type

April 8.00 15 Student --> April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student --> Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student --> Charlie 7.50 20 Student

The special pattern END matches after the last line:

END { print "Processed", NR, "records" }

April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

[End of File] --> Processed 11 records

You can keep track of values with variables that you define:

$3 >= 16 { emp = emp + 1 } END { print emp, "employees worked 16+ hours" }

April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

[End of File] --> 2 employees worked 16+ hours

{ names = names $1 " " } END { print names }

April 8.00 15 Student

Bill 10.00 30 Student

Charlie 7.50 20 Student

[End of File] --> April Bill Charlie